Dr. Stephen Powell PhD: Innovating the development of Work Focussed Learning in higher education

2.1 Section Summary

This section identifies the concepts and theories that have informed my reflections, analysis and evaluation of my work selected for this claim. They were identified through a process of reflection in the writing up of my claim, are introduced here as an overview, and are revisited in subsequent sections where I apply them to my practice.

2.2 Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

Figure 3 is an illustrative diagram showing the concepts (blue) with related key theoretical approaches and authors (yellow) that have been most valuable to me in identifying my original contribution to knowledge and practice innovating on Work Focussed Learning in higher education (HE). Although theoretical approaches are attributed to a particular concept, they are not restricted to a particular cycle of action research. These concepts and theories are introduced in turn.

Figure 3. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

2.2.1 Organisation of Teaching

In my role as the Ultraversity Project Manager (thesis table 1, 21-22), I had the opportunity to establish a new approach to the organisation of the delivery of a degree programme that used the model of Work Focussed Learning [P20 p97; P21 p66]. This is the focus of my first original contribution to knowledge: the conceptual development of new working practices in HE that delivered the model of Work Focussed Learning.

In practical terms, managing the Ultraversity project using an action research (AR) approach meant that choices about the organisation of teaching for the model of Work Focussed Learning was shared with those undertaking the work of teaching and supporting the students.

Although not known to me when I adopted an AR approach, there is a relationship to systems thinking which was introduced to me when I joined the Institute for Educational Cybernetics in 2007. Flood (2007, 117-143) highlights this connection; he makes the point that thinking in terms of whole systems develops the basis on which to undertake action research. This requires an understanding about the inherent complexity of social systems brought about by individual interpretations and the relationships between different parts of a system rather than seeing ‘problems’ in isolation that can be directly controlled. Modelling of a situation to a useful level of generalisation is a tool of systems thinking that is of great help to action researchers.

Reflecting on my experience managing the Ultraversity project, I have found Seddon’s analysis informative, particularly his critique of ‘deliverology’ (2008, 108-120), as an approach to the improvement of the public services, championed by Sir Michael Barber when head of the Blair governments Delivery Unit. Deliverology is founded on the idea that hierarchical target setting and monitoring, a command and control approach, leads to improvements. It is argued by Seddon, and I agree, that command and control is detached from the reality of the context in which the work is being undertaken resulting in poor decision making, and contributing to ineffective organisations (ibid., 70-71).

These ideas are explored further in Section 3, Organisation of Teaching.

2.2.2 Innovative Curriculum Design

In my role as curriculum innovator and implementer of curriculum design (thesis table 1, 21-22), I led the development of a strategic mechanism in the IDIBL Framework [P23] designed to bring about cross-institutional adoption of the model of Work Focussed Learning. This is the focus of my second and third original contribution to knowledge: a strategic mechanism to bring about cross institutional adoption of the model of Work Focussed Learning; and a cybernetic analysis of the pedagogy of the model of Work Focussed Learning in delivering a personalised curriculum.

The concept of Variety Management is important in Cybernetic analysis and is used as a way of thinking about the complexity of a system. This idea as applied to the regulation of complex systems was developed by Ashby and applied to the management of organisational structures by Stafford Beer (1985) in his Viable System Model (VSM) for control between different parts of a system and its environment, constituting feedback loops.

An analysis of the pedagogy of the model of Work Focussed Learning, using the cybernetic concept of variety, illustrates how the curriculum design addressed the challenge of how to personalise a curriculum for the complexity exhibited by numbers of diverse learners, within limited resource constraints.

I use these ideas in Section 4, IDIBL Project – A Cybernetic Analysis of a University-wide Curriculum Innovation.

2.2.3 Collaborative Curriculum Change

In my role as a project manager, I sought to bring about collaborative curriculum change using the IDIBL Framework (thesis table 1, 21-22). I undertook an analysis of institutional barriers to adoption of the model of Work Focussed Learning through reflecting on this experience, and through gathering empirical evidence from colleagues. This is the focus of my fourth original contribution to knowledge: critical analysis of institutional barriers to adoption of the model of Work Focussed Learning.

The change process that has been at the forefront of my practice has been informed by Communities of Practice (Wenger 1999), which is based on the idea that negotiation of meaning and reification of terminology are the heart of the development of a community with a shared practice, and within a common domain.

More recently, I have better understood this dimension through the idea of Teaching & Learning Regimes (Trowler 2008, 61-114) in HE, where the subject group level is identified as the common enterprise around which individuals and groups coalesce and where change can happen. This is explored in Section 5, Coeducate Project – The Challenge of Radical Curriculum Innovation in Higher Education.

2.2.4 Radical Curriculum Innovation

In Section 6, Summary of Conclusions and Reflections, I apply the theory of Disruptive Innovation (Bower and Christensen 1995) as a lens to consider my work in curriculum development, and undertake an analysis of the challenges that may be faced by a radical curriculum innovation in HE at an organisational level. I invite the reader to view the sections of the PhD through this lens by introducing their theory here. This is the focus of my fifth original contribution to knowledge: critical analysis of the challenges faced by radical curriculum innovation in higher education.

2.2.4.1 Theory of Disruptive Innovation

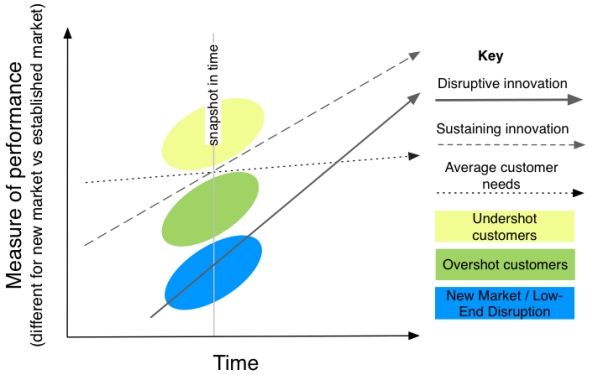

In their work on business innovation, Bower and Christensen (1995, 45-49) identify the dimensions of time and performance as being key to explaining the take-up of innovations, and these are used as the axis of the chart in Figure 4. In their early work the term technology is used but is replaced by innovation, typically a combination of technology and a new business model that exploits it and its potential for rapid further development, and hence ‘disruptive innovation’ is the term I shall use.

Figure 4. Disruptive Innovation (adapted Christensen and Raynor 2003, 44)

For the purpose of this thesis, Figure 3 is a synthesis and simplification of several charts that are used to explain the theory of disruptive innovation. For a particular context, there will be a complex relationship between customers, the performance characteristics of products and services in particular market segments, and the capabilities of organisations operating or seeking to operate in those markets, and these will change over time. For example, what is one organisations’ sustaining innovation may be for a different organisation a disruptive one. As customers’ circumstances change, the performance characteristics that attract them to one product or another may also change.

Bower and Christensen make a distinction between ‘sustaining’ and ‘disruptive’ innovations, and these are explained below.

2.2.4.2 Sustaining Innovations

Sustaining innovations are typically incremental, but may be radical innovations that enhance an existing product or service along a performance trajectory that meets the demanding requirements of existing, mainstream, and in particular, top end customers who are prepared to pay for better performance.

Christensen and Roth (2004, 9) identify two classes of existing customers for whom sustaining innovations impact, “undershot customers, for whom existing products and services are not good enough, and overshot customers, for whom existing products and services are more than good enough”. In Figure 3, the dotted line represents average customer needs, gradually increasing over time, while the dashed line represents the improving performance of the product or service over time, typically at a faster rate than the average needs of the customers, and above or below the dashed line different customers will be overshot or undershot depending upon their particular needs relative to the performance of the product or service. For example, at a particular snapshot in time, the yellow shaded area represents the top end customers who are constantly demanding better performance and, as valued customers, act as force for product performance improvement; these are undershot customers. The sustaining innovation will typically attempt to close the gap between the product’s current performance and their demands. On the other hand, some customers, would be paying for performance in a product that is more than they can utilise, and may be happy to compromise on the performance for a more usable or reduced cost product that meets their particular needs; these are overshot customers represented by the green shaded area.

2.2.4.3 Disruptive Innovations

Disruptive innovations by contrast do not attempt to bring better products to established customers. Instead, they combine a new technology that has the potential to evolve rapidly, with an innovative business model. This brings a new value proposition to the market with new performance characteristics that appeal to a different set of consumers or meets the needs of existing customers for established products or services but in a different way. In Figure 3, these currently unserved or nonconsuming customers are represented by the blue shading. However, if over time the new performance characteristics improve sufficiently to meet the needs of existing customers who are overshot by their existing suppliers products, then a disruptive innovation can be identified that attracts customers represented by the green shading.

However, over time, as the performance of these new products and/or services undergoes rapid improvement, they come to offer performances that go beyond meeting the needs of the incumbents’ low end customers, and increasingly attract their mainstream and may even, eventually, come to meet those of their top end customers as well (Bower and Christensen 1995, 44).

2.2.4.4 Application of Disruptive Innovation Theory

The motivating question that Christensen’s theory addresses is how is it that well run market leading companies (the incumbents) that listen to their customers, innovate accordingly, have good marketing and are financially well managed, can still be overthrown by upstart new companies (the disruptive innovators) – even though they are aware of them and can see what they are doing.

The initial reaction of current market leaders to an emerging disruptive innovation is that the product or service is inferior to their offering and if it attracts any of their customers, they are their least profitable low-end customers and so can be ignored. However, as the disruption continues to improve and begins to attract more of their overshot customer base, the market leaders still fail to react, retreating further into their top-end and most profitable but now shrinking customer base. So the question still remains: why do they not respond before it is too late?

According to the disruptive innovation theory, derived from observation of many cases drawn from different fields, the reason why market leaders can be overthrown by these new upstarts is that they have strong inbuilt filters that weed out any innovation proposals that do not directly enhance the current products or services they offer to their existing markets – they do not fit the elements of the existing business model (Johnson, Christensen, and Kagerman 2008, 3-5):

- the customer value proposition that meets a customers need to do something;

- profit formula for the creation of value for the company itself;

- resources required to deliver the customer value proposition; and

- established business processes.

The filters are not only the application of economic arguments and analysis of business models, but are also cultural in the broader sense of incumbent employees wanting to further develop rather than abandon their existing knowledge and skills, and processes and practices. Indeed, the arguments used when applying the filters are couched in terms of looking after the interests of established customers based on sound market research, supported by well prepared business cases, and are thus hard to argue against as exemplars of good business practice. In addition, from a financial perspective, disruptive innovations, “look financially unattractive to established companies” (Bower and Christensen 1995, 47) as their potential revenues and profit margins are relatively small. However, the incumbents’ existing cost structures, required to support and innovate existing products, are high and enhancing innovations are justified by the premium prices that their most demanding top end customers are prepared to pay. Any disruptive innovations that manage to escape the inbuilt filters are quickly deprived of the resources needed to get to new markets, in favour of more ‘important’ existing products and markets:

Innovations that conform to the business model are more readily funded. Organizations sometimes reject an innovation that emerges to address a new need in the market, but doesn’t fit these four elements of the business model. But the organization more frequently co-opts such innovations by forcing them to conform to the business model in order to get funded. When this happens – funding only flows to innovations that sustain or fit the business model – the organization loses its ability to respond to fundamental changes in the markets that it serves. This is what has happened to many universities (Christensen, et al.., 2011, 32).

The conclusion that Bower and Christensen (1995, 52) reach is that in the cases where a company has succeeded in introducing a disruptive innovation, it has been done by setting up an independent organisation.

It is therefore, a difficult task to distinguish a disruptive innovation from a sustaining or potentially sustaining innovation until one has the benefit of hindsight. Often the same technology development can be used to achieve both ends, so a new technology alone, even with potential, does not provide a sufficient decision criterion. Bower and Christensen suggest two questions:

- does the innovation meet the needs of a new set of customers? and

- does it have a lower profit margin than existing products?

A last note of caution offered is that once a disruptive innovation is established the temptation is to merge the innovation back into the parent organisation, but this should be resisted to avoid the resulting clashes about which model gets resources at the expense of the other.

It is arguable that technologies that make online, distance learning possible are a potential enabler for disruptive innovations in the educational field (Christensen, et al., 2011, 3). However, it is not simply a matter of technology but the overall ‘package’, which is offered to a customer, that creates a sustaining or disruptive innovation.

The model of Work Focussed Learning using Internet technologies combined with a different pedagogical and business model, by creating a new offer to non-consuming customers and potentially to overshot customers also, arguably provides a example of a disruptive innovation in HE.

2.3 Application of Concepts and Theories to Practice

In identifying concepts and theories to apply to the past ten years of my work, there are inevitably choices to be made about what is selected and how it is presented. Through reflecting on my practice, I identified the most significant aspects, which are presented in a table at the beginning of Sections 3, 4 and 5 along with a portfolio reference.

The key concepts and theories discussed above are applied to my practice to bring coherence, explanation and meaningfulness. In each section I will:

- set out the analysis that initiated my action;

- describe my practice and the actions I took;

- apply concepts and theories to support my analysis;

- evaluate and critically reflect on my practice;

- set out my original contribution to knowledge; and

- identify influences on future cycles of action.